MOMENTS, MEMORIES and MADNESS with STEVE CAMERON: Jerry Sloan’s last dance left lots of defensive marks

Surely you watched “The Last Dance,” the 10-part series on what made Michael Jordan so special.

At the very end, you saw MJ hitting the game-winning shot that clinched the Bulls’ sixth NBA title — and drove a dagger into the Utah Jazz.

It was a bitter finale for the Jazz, who felt they were better than Chicago in that 1997-98 season, and believed that a few critical officials’ calls in the fateful Game 6 cost them a chance to win their first championship.

You can argue whether or not Jordan illegally pushed off defender Bryon Russell on the final shot, but with the hindsight of tape, it’s clear that ref Dick Bavetta totally blew two shot-clock calls — one denying Utah a bucket and the other handing a late basket to the Bulls that shouldn’t have counted.

Just those two calls made a five-point difference in what turned out to be a one-point game.

As the sports editor of the Provo (Utah) Daily Herald, I was writing an analysis column on that game, while Doug Fox — our Jazz beat writer — handled the game story.

DOUG WAS as shocked as I was about how those shot-clock calls had been so obviously missed (not to mention Jordan’s push on the last play).

Later on, Doug also unearthed a great story about Bavetta’s role in the game — a tale that carried over into the next season.

During a conversation with Salt Lake City radio host Spence Checketts, son of former Jazz CEO Dave Checketts and once an NBA scout himself, Spence told Doug about a remarkable conversation.

Checketts explained that he’d heard reliably from an NBA coach (Jazz boss Jerry Sloan himself, maybe), that the first time Bavetta called a Utah game the following season — in Phoenix, as it happened — the ref actually asked Sloan and Jazz players John Stockton, Karl Malone and Russell if they could meet him in a hotel room.

Bavetta wanted to apologize for his mistakes in that playoff game.

What’s interesting beyond that, however, is how each of the four Jazz participants reacted — every one of them perfectly in character.

Stockton, who was still angry, reportedly just turned and walked out of the room.

Malone and Russell listened calmly, accepted the apology but otherwise did not do anything dramatic.

Sloan, though, was incensed by Bavetta’s admission of errors in a game that meant so much, and told the referee...

“Get the f…k out of this room!”

THAT WAS Jerry Sloan.

Hard-nosed. Old-school. Take no crap.

Offer no excuses.

Sloan passed away on Friday at age 78 after a battle with Parkinson’s. He will be greatly missed — and part of the reason is that men like Jerry just don’t pass our way so much anymore.

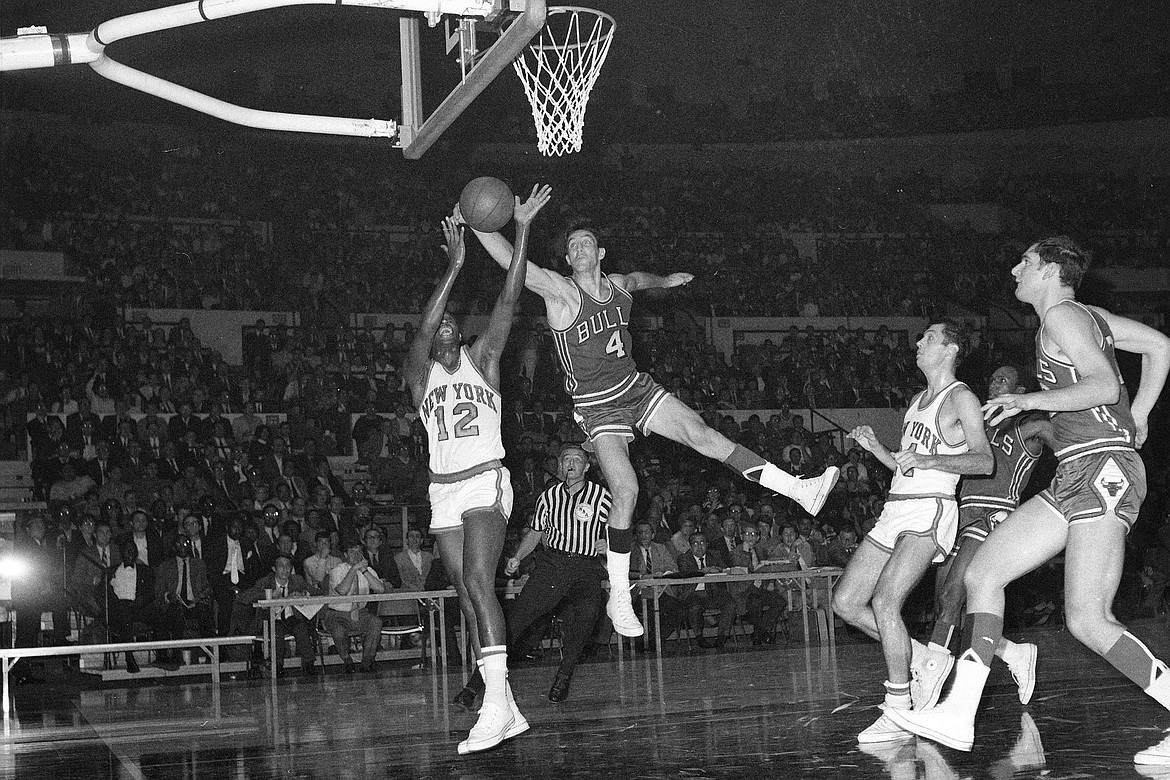

As a player, he was the brand-new Bulls’ first pick in the 1966 expansion draft, and through sheer defensive intensity (lot of elbows on his 6-5, 195-pound frame) and knocking people down to get rebounds, he became known as “The Original Bull.”

In fact, it was Sloan’s No. 4 that was the first to hang in the rafters of Chicago Stadium — not Jordan’s famous No. 23.

As a coach, he ran the Jazz bench well into his 23rd season, and had a losing record only once. His Jazz won more than 50 games 10 times, a feat matched only by Phil Jackson and Pat Riley.

Sloan is fourth on the list of NBA coaches with 1,221 victories — yet he never won a championship or was named Coach of the Year.

But I promise you ...

He didn’t apologize to God on Friday.

NEVER, BECAUSE Jerry always gave everything his heart and soul.

He left it all out there.

Jerry Sloan was the working man’s coach from McLeansboro, Ill., one of 10 children raised by a single mom, taught to get up in the dark, do farm chores and then walk 2 miles to school for basketball practice at 7:30.

There aren’t many hilarious anecdotes about Sloan, for the simple reason that he took his sport and his job seriously.

In all his years with the Jazz, the funniest thing he ever said was in response to a question about Stockton injuring his finger during a game.

A reporter asked: “Which finger?”

Sloan replied: “The one on his hand.”

Jerry was at his best when roasting his players to the media, because in the Stockton-Malone era, he knew they were awfully good and he didn’t want any lax attitudes.

“You’d think for all the money these guys make, they could manage to run up and down for a full two hours,” he said once, after the Jazz won a game in which they’d led by 38 points after three quarters.

To Sloan, coasting through an easy fourth quarter was stealing money from the organization and from the fans.

STILL, HIS players both loved and respected the farmer in charge (he once had a collection of 70 tractors).

Doug Fox attended the first day of the Jazz’ preseason workouts in Boise prior to that 1997-98 season.

Malone, as he was prone to do, was ranting about how he’d been dissed by owner Larry Miller (who said Karl had lost a step), and was carrying on about how center Greg Ostertag had arrived out of shape.

As usual, Karl had a media audience and he was in full flow.

Here’s the account Fox gave of what came next...

“Malone is the only player left. Sloan pops his head in and surveys the scene. Sees his star working himself into a lather.

“Jerry yells out: ‘On the bus ... now!’

“Now some people would be mad to be cut off in that situation. But Malone popped right up, excused himself and ran out. That was an example of how much he respected Sloan.”

SLOAN WAS inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in 2009, in the same class as Stockton, his record-breaking point guard.

Jerry chose Charles Barkley to give his introduction speech for the Hall, which tells you something about how respected he was throughout the sport.

Over this weekend, tributes have poured in — universal praise for a player and coach who was honest and always willing to work, even when it was the hard way to go.

San Antonio’s legendary coach, Gregg Popovich, probably spoke for the entire hoops community with his message...

“It’s a sad day for all of us who knew Jerry Sloan. Not only on the basketball court but, more importantly, as a human being. He was genuine and true. And that is rare.

“He was a mentor for me from afar until I got to know him. A man who suffered no fools, he possessed a humor, often disguised, and had a heart as big as the prairie.”

My own favorite memory of Jerry involved Michael Jordan.

The Jazz were preparing to play the Bulls in the Finals, we were alone in a hallway, and so I asked him: “Coach, what kind of defender would have the most luck guarding MJ?”

Sloan described an imaginary defensive player — height, strength, quick, tough, relentless — and when he got done, I said: “That mythical player sounds an awful lot like you.”

Jerry actually smiled (a rare moment for my mental scrapbook), and said, kind of sheepishly: “I sort of wish I’d had a shot at it.”

Then, as we were walking away, he added: “Mike would have gotten his points, but he would have spent a long time in the tub afterwards.”

I’d bet on that.

Even Jordan would have had an unpleasant night at the office against Jerry Sloan.

Rest in peace, Coach.

Email: scameron@cdapress.com

Steve Cameron’s “Cheap Seats” columns appear in The Press on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. “Moments, Memories and Madness,” his reminiscences from several decades as a sports journalist, runs each Sunday.

Steve also writes Zags Tracker, a commentary on Gonzaga basketball, once per month during the offseason.